What was done in desperate English times with the best of intentions created a legacy of painful Canadian question marks. They are the so-called Home Children and their descendants.

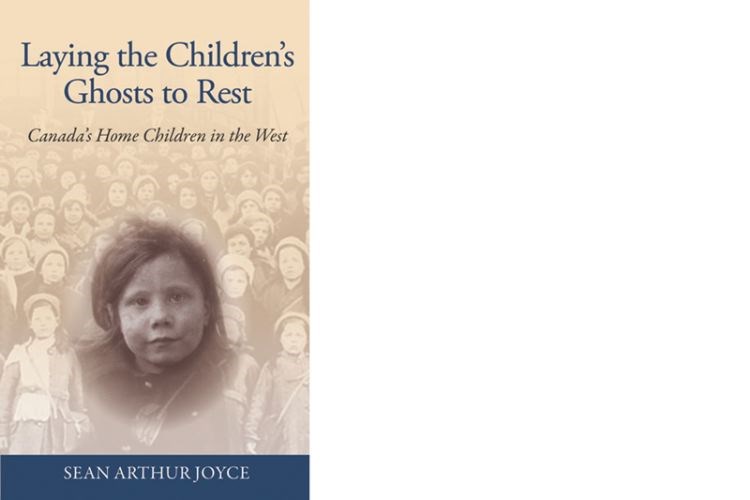

A new book by one of those descendants is calling his peers out into conversation. Sean Arthur Joyce has become a genealogy sleuth and family history detective in the search for his own personal background, and he wrote his experiences into Laying the Children's Ghosts to Rest.

"These were kids in orphanages in the U.K. or the children of unwed mothers, or poor families that had limited chances in life with a child, so these kids were sent to the colonies to families they recruited in Canada and Australia especially," said Joyce.

Between 1869 and 1948, about 100,000 such children, from babies to teenagers, were dispatched to Canada. The laws and social thinking of the day were that the records of these disconnected children should be sealed, if there were any records at all. Church organizations were often the intermediaries, adding another level of bureaucracy and shroud to anyone attempting to seek out information later.

And seek they did.

"My grandfather Ceril William Joyce was sent over by the Church of England in 1926," said Joyce. "Luckily he was already 16 when he arrived so he only had to serve three years, working on northern Alberta farms as his indenturement until he turned legal age."

If this scenario sounded more like a prison sentence than loving domestic arms, it's because that was the case in a great many of these orphan intakes. The Canadian homes agreed to these children out of a desire for the love of children in some cases, but just as many were interested in the slave farm labour. Some were even interested in acting out abuse on these boys and girls who had no one looking out for them once they were deposited on the doorstep.

The aftereffects of Home Children are similar to those who endured residential schools, Joyce discovered. There is a pattern of trauma response: alcoholism, suicide, inability to hold down jobs, inability to form positive relationships, and so on.

"My grandfather would never speak about it, despite efforts from my father to pry the details out of him, so I grew up with this nagging question: why? As an older Home Child he knew what was happening to him. Why hide such pivotal point in your personal story?," Joyce said. "As a journalist myself, and a writer, I decided it was time to get into it."

He learned about how social pressures pried babies from the arms of loving mothers who, today, would get support to raise the child on her own without undue difficulties. He learned about upstanding social agencies on both sides of the Atlantic that tried their best to help orphans. He learned of families made stronger and lives blown apart.

He also learned of his own past. One scant thread of information about his grandfather's past in England became the only lead Joyce had to focus on, so he went to the source.

"Five years ago my wife and I travelled to England and met someone who was descended from a great-great uncle," Joyce said. "And because he'd done so much research himself, he knew where the family had originated in Dorset County, working as millers and farmers for nearly 500 years. We went from zero to half a millennium in almost one instant."

The jackpots and dead ends, the successes and tragedies, the best hopes and darkest consequences of the Home Child program are stuffed into the pages of Laying the Children's Ghosts to Rest. He also has a slide show accompanying the book. Everywhere he makes his presentation, he is ready to meet more people just like him, and delve deeper into the human historical puzzle that has pieces scattered all over Canada by this point.

"My record so far was an audience of 50 where more than a dozen were descendants of Home Child kids, and they all have stories to tell," Joyce said. "I have met one actual still living Home Child in person and another on the phone. One thought it was the best thing that ever happened to him; the other suffered a lot of unhappiness. In many cases it was a recipe for abuse. I don't think the people who set up these programs were evil, in fact to the contrary, they were trying to help society. Many were progressivists. But there were just so many variables and motives that weren't controlled along the way. So that's what I get into: how has this affected us as a people?"

Joyce will be live, with book and slide show at the ready, on Wednesday at Books and Company. It is a free show starting at 7 p.m.